What Every Cash-Secured Put Seller Must Do in the First Hour After Assignment (Most Skip Step 2)

Tomorrow, I'm sending my list of new put trades.

Read this first.

This is the complete tactical guide for managing an assignment and turning it into income.

Ok, so you’ve been assigned.

That knot in your stomach is a normal reaction. I still feel it sometimes.

But for a disciplined investor, assignment isn't a bug in the system — it’s the system's primary function.

And it’s definitely not the end of a trade; it is the beginning of the real work.

Here is exactly what to do:

The First 30 Minutes: Your Post-Assignment Checklist

Panic is a terrible financial advisor.

When you see that assignment notice, don't rush to sell. Instead, work through this tactical checklist.

Step 1: Calculate Your Real Cost Basis.

This is the most critical step.

You did not just buy the stock at the strike price.

You bought it at the strike price minus the premium you were already paid.

That premium is a permanent discount on your acquisition cost.

The formula is non-negotiable:

Cost Basis per Share = Strike Price - Premium Received per Share

Let's use a textbook example that we’ll track.

Say you sold one put contract on Ford (F) with a $14 strike price and collected $0.60 per share ($60 total).

Ford was trading at $15.

A few weeks later, some bad news hits the auto sector and Ford drops to $13.

You get assigned.

You are obligated to buy 100 shares at $14, for a total cost of $1,400.

But you already pocketed $60 in premium.

Your actual cost for those 100 shares is $1,340.

Your true cost basis isn't $14. It’s $13.40 per share.

This number is now your breakeven point, and an anchor for every decision you make from here on out.

Step 2: Re-evaluate the Asset: Bruised vs. Broken.

Now that you own the stock, you must determine if the company is merely bruised or fundamentally broken.

This is the hardest part, and it requires brutal honesty.

1). Broken Thesis:

This is a company-specific, likely permanent issue.

Think accounting fraud (Enron), a disruptive technology that makes its product obsolete (Kodak), or a catastrophic failure (a biotech’s only drug failing Phase 3 trials). A broken thesis means the original reason for your investment is gone.

The smart move here is often to liquidate the shares, take the loss, and preserve your capital for a better opportunity.

2). Bruised Thesis:

This is typically a temporary or market-wide problem.

Think a broad market correction, a hawkish Fed announcement that spooks everyone, or a decent earnings report that the market hated for irrational reasons. The company itself remains strong. If the thesis is only bruised, the price drop is a temporary condition. This is the scenario our strategy is designed to exploit.

Knowing the difference is half the battle.

The other half is having a system to identify the highest-quality "bruised" candidates before the market does.

My proprietary VADER screen is that system, running 3,217 optionable stocks through a 16-point quality gauntlet. This is the exact screening process I use to generate my weekly picks.

If you want to see which high-quality companies pass the test this week, it might be time to join.

The Two Paths Forward: A Tale of Two Assignments

Now, let’s examine how this plays out along two different paths.

One is a clean, textbook case.

The other is a more common, grinder of a trade that tests your patience.

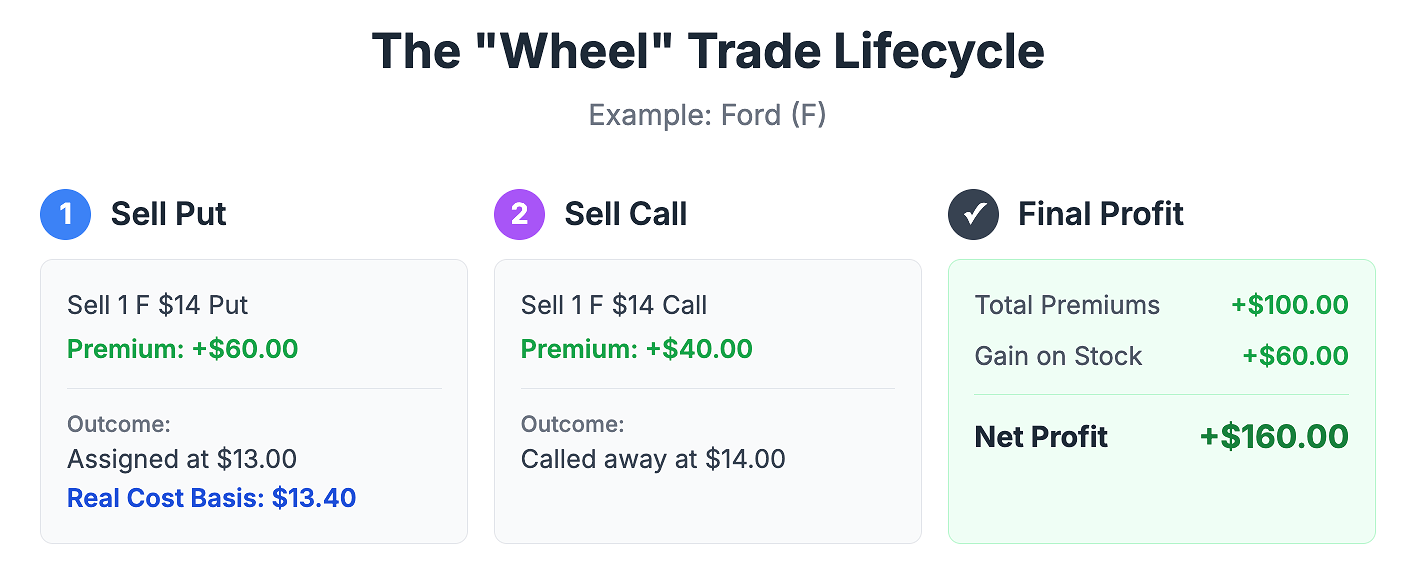

Path 1: The Textbook Wheel (The Ford Example)

This is the ideal scenario where the stock cooperates.

→ You were assigned Ford at a $13.40 cost basis.

→ The stock is at $13; Believing the thesis is merely bruised, you begin the income phase by selling a covered call.

→ You sell a one-month call with a $14 strike and collect another $0.40 per share ($40).

The stock rallies back above $14 and your shares are called away.

This is beautiful when it happens. You turned a drop into a profitable, all-cash transaction.

But what if the stock doesn't bounce back so nicely?

Path 2: The Grind-It-Out Landlord (A More Realistic Example)

→ Let's say you sold a put on a quality industrial company—we'll call it DE—at a $380 strike and collected $7.00/share ($700) in premium.

→ The stock dips to $375 and you're assigned.

→ Your cost basis is $373.

But instead of bouncing, the market stays weak.

Over the next few months, DE drifts down to $360.

A "bruised, not broken" company. You are now the landlord of a property in a temporarily soft neighborhood.

Your job is to patiently collect rent until the market recovers.

Month 1: Stock at $365. You sell a $375 call for $4.00/share ($400). It expires worthless. Your cost basis is now $369.

Month 2: Stock at $362. You sell a $375 call for $3.50/share ($350). It expires worthless. Your cost basis is now $365.50.

Month 3: Stock at $368. You sell a $375 call for $4.50/share ($450). It expires worthless. Your cost basis is now $361.

After three months, you have collected $1,200 in cash flow from your 100 shares.

Your breakeven price has been ground down from $373 to $361.

The stock, still trading at $368, is now well above your new cost basis.

You've manufactured a profit margin out of thin air while waiting.

Now you can sell your next call with a much higher probability of success or simply sell the shares on the open market for a gain.

This is the reality of the strategy. It's not always fast. It is a methodical, industrial process for extracting cash from an asset you own.

The Hard Questions & The System's Answers

"But what if the stock just keeps dropping?"

This is the primary risk.

The premiums you collect can be overwhelmed by a deep capital loss. This is why the quality of your target is everything. Your primary defense is not what you do after assignment, but the screening you do before selling the put. My VADER system is built to weed out fundamentally weak companies. We are targeting businesses that have the financial strength to weather a storm, so we have time for the "grind-it-out" scenario to work.

"What's the right move when I'm deep underwater on a position?"

Let's say in our DE example the stock had dropped to $340, and your cost basis is still up at $373. Selling a call at your $375 breakeven would yield almost nothing in premium.

Here, you face a tactical choice:

Wait Patiently: Sell far out-of-the-money calls for pennies, slowly chipping away at your basis.

Sell a Call Below Your Basis: You could sell a $360 call for a much larger premium. The downside is that you are agreeing to sell at a loss if the stock recovers to that level. The upside is that you generate more immediate income and could lower your cost basis faster. This is a trade-off between time and money, a decision we often face in the "Live Lab."

"How do I learn to make these calls under pressure?"

The theory is straightforward.

Executing it with real money on the line while your account is in the red is hard. It tests your discipline.

This is precisely why I structure The Multiplier as a live trading lab.

When a trade gets messy, I don't hide it. I put it under the microscope. We analyze the math of rolling, the trade-offs of selling a call below our basis, and the signals that tell us when to cut a loser.

Seeing this process play out in real-time builds the muscle memory and conviction you need. That is the only way to truly learn.

This is the framework.

This is the mental model you need.

Now you're ready for the tickers.

Look for the list of new Cash-Secured Put candidates in your inbox tomorrow.

We’re not just finding trades; we’re building the income machine, one quality component at a time.